|

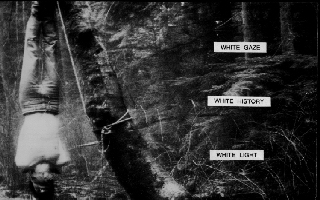

The comparison of these examples with my own experience arises from acknowledgement that many First Nations writers have also had to become extensively literate in an enveloping foreign culture in order to be just barely heard and to try to break an easier trail for the next generations. Trailbreaking involves three main tasks: negotiating the removal or reduction of often overwhelming academic and professional requirements and barriers that have little or no relevance to our cultural practices or histories; caching resources along the way in the form of speaking with our own cultural voices in the documentation of our struggles, successes and failures; and giving honour and acknowledgement to the previous First Nations trailbreakers and their allies who made our present work possible, even as far back as Occom and Apes. They fought for the rights of ts of their people by writing in White Christian language and vocabulary to a White audience because it was the only language that White culture would acknowledge.

In the recent past, especially over the past twenty years, we have seen examples of the often dramatic successes that have been brought about by this multi-generational struggle, but these are always accompanied by tragedies that will not let us rest. Understandably, as with any long and often exhausting struggle, there are those in First Nations communities, especially among some of the lucky young who have benefited from this work in a consistent and deserving way, that now are able to question the need for continued struggle to change White attitudes and value systems. Thankfully, they have been well prepared to begin speaking in their own voices to their own people.

But twenty years of success have produced only a fragile patchwork of understanding and commitment within the non-First Nations arts community. This is due to the fact that twenty years is a very short time for us to heal deep cultural wounds, to revive teaching practices, reassemble dispersed historic cultural materials, and renew inspiration from our own languages compared to the huge and growing body of hundreds of years of continued work that supports and validates the White arts community.

In the broad diversity that may be loosely conceptualized as the non-First Nations Canadian contemporary arts community there are certain strong threads common to almost all its elements. Each particular self-defined community within it, whether formed through regional, thematic, theoretical or stylistic commonalities, relies on a strong relationship with a history of origin that stretches far back beyond the time of contact with Turtle Island. These relationships may be oppositional - working to revision this history, collaborative - in support of the development of certain historic movements, or, most often, varying degrees of both. Whatever the approach, there are massive amounts of historic materials that can be drawn upon to support all manner of strategies of contradiction, ambiguity and continuity by non-First Nations artists. These threads are also evident in the range of institutions, agencies and professions that support and thereby, to a certain extent, regulate the practices of artists.(3)

One of the basic requirements for entry into arts professions in Canada is to have accredited and demonstrable understanding of European art history and the subsequent preservation and contemporary expression of it in Canada, the U.S. and Europe. This is also true of artists who support their practice by working in other arts professions such as teaching, etc. Thus, arts professionals must be fully equipped with a set of historic resources that sometimes formed the foundation for, arose out of or were developed parallel to the active and unapologetic eradication of living First Nations cultures and the exclusion and silencing of the voices of living First Nations cultural practitioners; actions which are still in living memory for some, and form a large part of the still-recent legacy of almost all First Nations. An ironic exception is the work of early (and not so early) anthropologists who practiced what they termed "salvage ethnology," collecting and documenting what they thought of as the last fragments of our living cultures before we would inevitably be extinguished. (A fragment of a conversation was related to me by a friend which took place with a highly respected and definitely well educated arts professional a couple of years ago: "Where did you get that amazing archival material [photographs, footage]?" "I made it myself this summer on my reserve.")

The well rounded accreditation of non-First Nations arts professionals for the most part does not require even a rudimentary understanding of First Nations post-contact political history, let alone the basics of of historic and contemporary First Nations cultural practices, and certainly not any of the most crucial understanding of how our unique languages and oratures shape and guide our diverse cultures. Thankfully, the professionalism and respect of many individuals in the non-First Nations arts community compels them to undertake personal research into these areas so that they have a deeper understanding of the rapidly growing community of First Nations artists with whom they are working and transforming the institutions in which they work. That understanding is however, inconsistent, idiosyncratic and fragmentary when examined across the broad scope of the general community of contemporary arts professionals. The political will of everyone in the arts community is now required to transform the academic art and art history community to ensure a consistent and growing focus on First Nations art and culture as a fundamental requirement of an adequate arts education for arts professionals in Canada.

Dr. Olive Dickason, a Métis elder, was awarded the Order of Canada in January of this year for her work in education. In education. In 1972, she earned a Master's Degree in Canadian Studies, taking as her topic the French and Indians at Louisburg. At that time, in order to negotiate her degree, she had to overcome a great deal of institutional resistance toward inclusion of First Nations topics in the study of Canadian history as well as negotiating recognition for herself as a Métis and as a woman in a field dominated by White men. They tried to insist that the histories of First Nations were topics suited only to the field of anthropology. The award recognized her crucial leadership over the past two decades in helping to establish the study of First Nations history into what is now one of the most rapidly developing fields of study in Canada. The Saskatchewan Indian Federated College, an independent college federated with the University of Regina, was established in 1976 and has experienced rapid growth ever year. In 1988, the University of Alberta established their School of Native Studies independent from their Faculty of Arts. One of the most important struggles for First Nations is to regain, rebuild and support fundamental roles for teachers in our cultures. The ability to transmit culture to a wide audience through diverse teaching strategies is essential to functioning in a self-determined way. A vital part of what occurs downstream from this is the support for and recognition of the work of First Nations people engaged in sustained, consistent and rigorous study, research and analysis of First Nations art and culture.

Unfortunately, most art history educators can still safely omit any references to First Nations art practice, and First Nations art history courses taught by First Nations people are still non-existent in many art education departments and institutions that perceive their offerings as adequate and well rounded. Every institution that has a mandate to serve or contribute to the general Canadian arts community must realize and act on the full implications of their responsibility. The most important task at this historic moment is to contribute to the re-establishment of the cultural leadership of First Nations people.

Twenty years of achievement toward an in-depth and self-determined focus on First Nations cultures is only a small beginning. Regaining our voices over the past two decades has only just begun to resolve centuries of imposed and corrosive silence. We are still swallowed up in the flood of non-First Nations culture. But Wacaskwa (muskrat) has returned from his long swim, bringing up to us a little piece of earth from which we are beginning to rebuild our cultural Turtle Islands.